LiDAR and Archaeology: Revealing What Lies Beneath

21 10 2025

Category: Archeology, Research infrastructure

Precise airborne scanning enables archaeologists to detect traces of ancient civilisations that are invisible to the naked eye. Bartosz Wojciechowski, an archaeologist at the Antiquity of Southeastern Europe Research Centre, University of Warsaw, explains how LiDAR is transforming archaeological fieldwork. Specialising in photogrammetric documentation and geodetic support of excavations, he shares insights into how this technology is changing archaeological practice.

INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES: What exactly is LiDAR, and why does it attract so much attention among archaeologists?

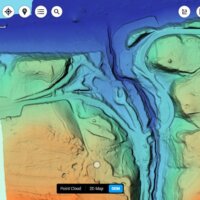

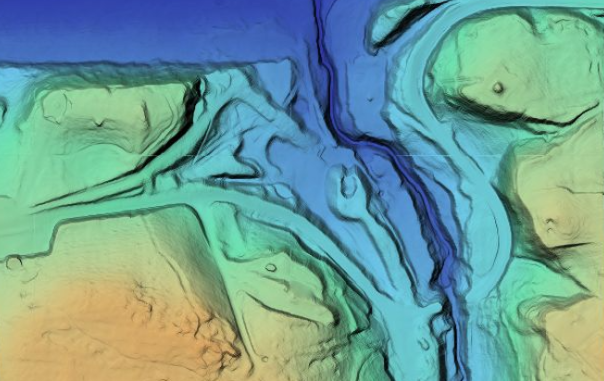

Bartosz Wojciechowski: LiDAR is a laser-scanning technology that allows researchers to create extremely detailed three-dimensional models of the Earth’s surface. It emits thousands of light pulses per second, and by measuring the time it takes for them to return to the sensor, we can accurately determine distances and topography. For archaeologists, this is a real breakthrough – LiDAR allows us to “see through” vegetation and uncover structures invisible in aerial photographs or on the ground. When combined with other data, such as that obtained through geophysical surveys, it provides a comprehensive and precise picture of both surface and subsurface features.

What does this mean for archaeological research in practice?

Thanks to its accuracy, laser scanning makes it possible to detect archaeological structures that were previously invisible and barely preserved. In many regions, archaeological sites are covered with dense vegetation, which has hindered their documentation for decades. LiDAR helps identify ancient roads, walls, terraces, and even traces of ancient settlements that have been almost entirely reclaimed by nature. This technology allows researchers to plan fieldwork far more precisely – before even setting foot on site, we already know where to look.

But LiDAR is not only useful for discovering new sites. It also enables highly accurate documentation of known ones, helping to monitor landscape changes, assess erosion, and plan conservation strategies. Importantly, data from a single flight can be analysed multiple times – in the future, new algorithms may reveal even more information hidden within the same dataset.

Where are you currently conducting research using this technology?

Our work is conducted in Bulgaria, at one of the most fascinating archaeological sites on the frontier of the Roman Empire – the legionary fortress of Novae, explored since the 1960s. LiDAR allows us to look at the site from a completely new perspective – quickly, precisely, and in great detail – revealing features that could easily have been overlooked before.

This research is part of a broader project titled “Living Forever the Past Through a 3Digital World – LIP3D”, which employs VR, AR and 3D modelling to reconstruct and digitally share archaeological sites. The Polish component of the project is coordinated by Dr Krzysztof Narloch. The results of LIP3D will enable both researchers and the wider public to explore ancient sites in fully interactive ways.

How does data collection using LiDAR actually work? Are there any challenges?

In the field, the LiDAR sensor is usually mounted on a drone that carries out a series of flights over the target area. Each mission requires careful planning – flights must take place in suitable weather and stable atmospheric conditions to avoid data distortion.

The biggest challenge lies in the terrain itself – dense vegetation or uneven surfaces make it crucial to choose the right scanner settings, calibrate the equipment, determine precise flight paths, and later process the data with expertise.

Is LiDAR difficult to operate?

It requires specialist knowledge – both in equipment operation and in data analysis. Raw LiDAR data must first be processed: filtering out noise such as vegetation and creating a terrain model. Only then can archaeological interpretation begin. Yet this is also the most exciting stage of the work – traces of the ancient world emerge from what at first looks like a cloud of random points.

What possibilities come with having your own LiDAR equipment?

It’s a major step forward. Having our own LiDAR system enables surveys and analyses over much larger areas – faster and with remarkable precision. It also opens new opportunities for collaboration with other research teams, both in Poland and abroad.

After completing the current project, we plan to use the new scanner at other sites studied by the Centre – in Bushat (Albania) and Risan (Montenegro). Both include difficult-to-access areas, and we expect the equipment to perform perfectly in those conditions.

The LiDAR used in the research was purchased as part of the “Living Forever the Past Through a 3Digital World – LIP3D” project, co-financed by the Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Warsaw.